The largest core theme across OM’s portfolio is things where supply is limited and where there is increasing demand. Most obviously, you’re probably sick of hearing OM harp on about the supply deficit in Uranium, while new nuclear power plants are being built in the developing world and existing ones having their lives extended in the developed world. However, it’s more pervasive than just Uranium – you see it in Shipping/Tanker (record low order books coupled with increasing tonne miles), or in some equities (TPL/JOE own specific plots of land, i.e. supply is fixed and they are seeing increased demand for its use), or even Bitcoin (slowing rate of supply, coupled with increased demand from investors/institutions), etc.

COVID-19 has brought many of these situations to the fore as demand is recovering far more quickly than supply can adjust. This is particularly the case in commodity-related sectors, especially where there have been years (or decades) of under-investment that have led to structurally under supplied markets. Unsurprisingly, OM has focused his attention on the markets where long-term demand growth is combined with a structural supply issue.

The tin market is one of the clearest examples of this. Tin is the smallest of the base metals markets and is used across a wide variety of products (i.e. the opposite of uranium, which has one use) and thus typically ignored by investors. Tin is often also used in tiny quantities in products – there are a couple of grams of tin costing <15c in your iPhone – but typically has no substitutes thus demand is very price inelastic. Tin also has a crazy history on the supply side with failed CIA stockpiling and a collapsed cartel resulting in oversupply for almost 45-years. All of the major suppliers are seeing substantial declines in their output, with most of the efficient and cheap to access tin having already been mined. Finally, though Western investors have limited ways to participate in the tin market, one is the producer with the best global tin deposit!

Demand for Tin

The potential long-term demand growth is the easy part of the equation for Tin. Tin’s primary usage is in solder, especially as the ‘glue’ for semiconductors. Tin is also used in chemicals (as a stabilizer in plastics), tin plate (tin cans), float glass (i.e. your windows, as tin is vital to the Pilkington process) and in batteries (for EVs), but typically makes up a small but vital component of the overall systems in which it is used. For example, a ‘tin can’ contains only 1-2% tin or an iPhone contains a couple of grams of tin yet it’s vital for the electronics and touch screen to work. This means demand for tin is largely price insensitive.

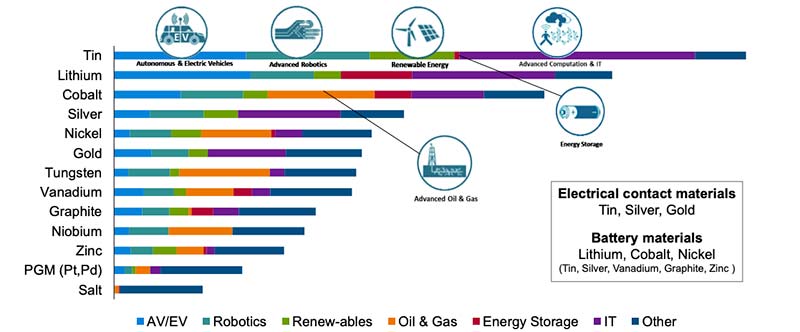

Tin’s primary use is for solder, especially in semiconductors where the electronic solder (which is 95% tin) joins the components. Over the last 15-yrs, despite the growth in electronics the demand for solder was constrained by miniaturization, i.e. the semiconductors in your phone became ever smaller requiring less solder. However, expected demand growth from the increased semiconductor content within electronics (phones, cars, etc.), as well as the growth in electronic technologies (think 5G and the “Internet of Things” or “4th Industrial Revolution”) is an order of magnitude higher than the loss from miniaturization. Tin is also vital to to new technologies, such as battery technology, robotic and electric vehicles, which was highlighted in an MIT study of key new technologies and the metals required.

Supply

Tin has been recognized as a strategic metal since it was first combined with copper to create bronze leading to the whole Bronze Age period! This strategic importance, combined with being the smallest of the metal markets (~300,000 tonnes annual production) has resulted in a crazy history!

After WWII, the CIA identified tin as a strategic metal that was required for artillery and naval guns, and early electronics, and which the Soviet Union was entirely reliant upon imports. This led to the US Defense and Logistics Agency (“DLA”) aggressively procuring tin until 1960, such that in thirteen years it had acquired over 350,000 tonnes of tin, or three-years of global annual production at the time! The DLA eventually gave up as its purchases had squeezed supply, causing price to rise and pushing the Soviets into major exploration, production and eventual self-sufficiency. The DLA subsequently liquidated this tin inventory and it took them until 2006 to do so. This huge forty-five year (!!!) secondary supply overhang limited the need for new tin exploration and production during this period.

While this was all happening the International Tin Council was created in the late 1950s. Over the course of twenty-five years, six separate International Tin Agreements were signed by thirty countries to limit production. While a key aim was to reduce fluctuations in the tin price, the majority of the members were producers and so the agreements contained increases in the targeted tin price. However, by 1985 the ITC ran into soft demand (damn aluminium cans!) and new tin discoveries in non-member countries (primarily Indonesia and Peru). This coupled with quota busting by ITC members led to a vastly oversupplied market and the ITC collapsed into bankruptcy in 1985. In its attempts to hold the tin price up, the ITC had run up liabilities of just under $1.5 billion (in 1985 dollars!!!) and held over 120,000 tonnes (or eight month’s global supply) of physical tin, as well as additional derivative purchases.

During the 1990s and 2000s while the DLA and ITC were slowly liquidating their tin inventory and China and Indonesia were ramping up their tin production the market was in surplus. This meant that the tin price was depressed and there was no incentive for producers to look for tin. After the secondary liquidations finally finished in the mid-2000s, the tin price rose only for Myanmar to plug the under-investment gap after ramping up production in the 2010s. China and Indonesia are the two largest producers in the market today, each representing 25% of supply, though production is down significantly from its highs. Myanmar represents 17% of global tin production and will have run out of tin in 2023!!

Finally, there’s a wrinkle in the way that tin is mined. The cheapest and most efficient way of mining tin is alluvial mining, where a river or stream bed is mined for deposits. This can be done artisanally in a similar way to gold pan-handlers and on a more commercial basis through dredging. However, the best alluvial mining sites (e.g. Myanmar, Malaysia, and Indonesia) have all seen significant production declines as they have mined most of their resource. This means future tin production will come from underground (hard rock) mining, which is more expensive, difficult and capital intensive and requires a significantly higher tin price.

In summary, you have a potential perfect storm for a non-linear rise in the tin price. On the supply side you have a market where massive secondary supply has limited exploration over the last 50+ years, existing suppliers are running out of material, and where the only viable method of mining is vastly more expensive and less efficient. At the same time, you have a material that is a tiny but key and not substitutable component of almost its entire end demand, and where technological changes are driving material demand growth in the coming years.

How is OM expressing it?

For Western investors there are currently only 2 investable producers; Alphamin Resources (AFMJF) and Metal X Limted (MLXEF). The difference between the two companies is stark!

The majority of OM’s exposure is to Alphamin Resources (AFMJF) who own ~80% of the Bisie tin mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo (“DRC”). Bisie is THE premier tin asset globally. It has the highest grade resource of major mines globally, is a lowest quartile producer, and currently produces about 4% of global supply (it is 8% of global reserves), with near term ability to expand production.

Alphamin is significantly cash generative at today's tin prices and is using its free cash flow to pay off its external debt (OM’s back of the envelope model suggests it’ll be debt free before year-end) and then potentially pay a dividend. The company has benefited from upgrading management at both the corporate and mine levels, and at today's tin prices will be generating close to a fifth of its current market cap in free cash flow this year. However, the single mine and DRC-related risks limit OM’s position size, though it should be noted that the DRC Government has a 5% stake in the mine.

Metal X (MLXEF) is Australia’s largest tin miner but is a marginal producer that expects to mine 10K tonnes of tin by 2025 and can barely make money even at today’s rising tin price. It is thus riskier and far more levered to a higher tin price, and as such a tiny position for OM.

Disclaimer: Nothing above represents a recommendation in any way,

shape or form so please don’t even think of trying to take it that way.

For added clarity, while Our Man is invested in all of the securities

mentioned that’s a terrible reason for anyone else to do so.

No comments:

Post a Comment