Given the all the news flow on alternative energy over the last couple of years, and the successful IPO of A123 Systems and the upcoming IPO of Tesla Motors, why would Our Man be expressing his interest (again) in the boring old Lead Acid battery companies that they’re likely to put out of business?

The simplest place to start is probably a simple thought experiment – think about all the times you’ve driven your car, how many times have you had battery problems? I’m guessing that the answer’s not many, irrespective of whether it’s hot, cold, snowy, sunny, rainy, etc. That’s the standard that we’ve come to expect from our car batteries. Now, think about your cell-phone or laptop and how many times you have had battery problems – I suspect it’s a whole lot more often. Yet, people seem to have pre-determined that updated versions of the same technology will be able to meet the standards we’re accustomed to at a price we can afford. The key here is my use of predetermined, as it seems to me that the overwhelming consensus (by industry, the government and the market) is that it has been decided that Lithium-Ion is the future of vehicular power, and such stocks should trade on that. To Our Man’s mind, that such a decision appears to have been made before the race is run is interesting but the fact that the market is already pricing it as a fait accompli into stocks is enticing! Is there a cheap option to be had for people’s assumption proving wrong or overly optimistic?

Overview

Currently, the major US Lithium Ion (“Li-Ion”) battery companies have barely any sales (e.g. A123’s revenue last Q was $25mm, with a negative gross margin) but significant market caps based on the expectation of the key role that they will play in our vehicular future. The major Li-Ion battery companies that I’ll be referring to are A123 Systems and ENER1 Inc, though I’m sure electric vehicle manufacturers like Tesla and Fisker will get a mention.

However, given the horrendous history of Lead-Acid battery companies and the seeming lack of innovation in lead-acid batteries, it’s easy to see why a new technology seems attractive. As such, current lead-acid batteries are a commodity product and though the industry is dominated by a small number of players, they have no real pricing power. I also feel the consensus ignores the obvious question; why should Lead-Acid batteries have seen any innovation until recently? After all, they do what they’re supposed to well and they do it cheaply.

Electric Vehicles – Li-Ion’s future

When I mention Li-Ion being our vehicular future, it is because of their use in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (“HEVs”. While this may bring images of battery powered cars to the forefront of our minds, there are in fact four primary classes of HEVs:

1. Micro Hybrids – Do not use an electric motor to drive the vehicle, instead use battery to:

• Stop/Start the Internal Combustion Engine (“ICE”)

• Power accessories (e.g. air conditioning, etc) when the ICE is off

• Uses energy from braking to recharge the battery

2. Mild Hybrids – Uses the battery for everything that a micro hybrid does plus:

• The electric motor is integrated into the ICE to boost power during acceleration

3. Full Hybrid – Uses the battery for everything that a micro hybrid does plus:

• The electric motor is separate from the ICE and is powerful enough to drive the vehicle. Typically, use the electric motor to launch from stop and start the ICE when needed, using both for acceleration

4a. Parallel Plug-in Hybrid: Same as full hybrid, but with a bigger battery pack that increases the Electric range, which means less reliance on the ICE.

4b. Series Plug-in Hybrid: Electric Vehicle that runs on battery power for 10-40miles then uses a small ICE to drive the power-train.

You’ll note that the first 3 classes of car are available today, with the 4th class being the much discussed Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle (“PHEV”) for which the Nissan’s Leaf and GM’s Volt are hoping to be standard bearers. Furthermore, despite the press attention, hybrid cars (in all their forms) make up an exceptionally small part of the current car market.

Historic Annual Hybrid Car Sales

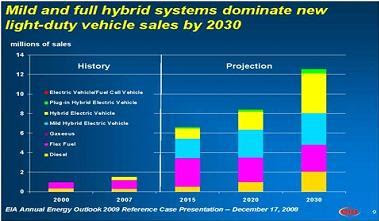

While this is expected to change, going forwards, despite all the attention on PHEVs they are not anticipated to make up a noticeable portion of car sales in the next 20years, with the majority of hybrid sales falling into the micro/mild hybrid category. While I’m using Energy Information Administration and DOE projections below, the projections from private consultants (e.g. Frost & Sullivan, etc) is similar.

Expected Hybrid Vehicle Market Size (Energy Information Administration/DOE)

Thus, it seems to me that in the medium-term Lead Acid (and any upgrades to it) only needs to be competitive in terms of power and cost in micro/mild hybrids rather than be able to power an electric vehicle tomorrow. For those who think Li-Ion is the battery of the future, I think you’ll be somewhat surprised by the results.

Friday, June 25

Thursday, June 17

Endowments – Part B: Why Our Man doesn’t love the current Endowment Model

As Our Man’s mentioned, he’s not the biggest fan of the endowment model and one of the reasons stems from the following question; are they really perpetual and permanent sources of capital?

Given that an endowment is there to support an institution (be it a foundation or a university) the level of risk that an endowment takes should be related to how the institution uses the annual. For example, Universities that get a significant percentage of their operating revenue from endowment disbursals (e.g. Princeton at c45%, Yale at c45%, Harvard at 35%, etc) should have different investment and risk objectives for their endowments than those where the disbursals represent a minimal amount of operating revenue. Larger endowments (in terms of disbursals as % of operating revenue) should be more risk averse than smaller ones, unless the institution is prepared to make significant cuts in its operating budget (e.g. by firing professors, doctors, etc or substantially reduce grants) every time there’s a noticeable fall in the endowments value. As such, can an endowment really be considered permanent when it provides a significant part of the operating income of the attached institution?

Illiquidity and being Short an Option

If we go back and look at the Endowment Model and how Harvard and Yale’s endowments have changed over time - we can see a reduction in fixed income and listed equities. Based on Mebane Faber’s work; at Yale between 1985 and 2008, Fixed Income (10.3% to 4%), Cash (10.1% to -3.9%) and Equity (67.9% to 25.3%) were all sources of cash. They were replaced by investments in Private Equity, Real Assets and Absolute Return strategies. This represents both a move towards more illiquid equity-orientated strategies and a subtle increase in leverage (as a result of investing in strategies, and outside managers, that employ leverage).

Unquestionably, one of Harvard and Yale’s great successes was realizing in the late 80’s and early 90’s that there was substantial illiquidity premium to be reaped by those investors who had a longer-time horizon. However, with the publicizing of the Yale model, and the move by others to copy it post-2000, does that illiquidity premium still exist?

Harvard and Yale’s macro call on the use of leverage has also proven to be successful – as investments that rely on leverage have benefited over the last 20years from the increased availability and low cost of credit. The use of credit and leverage has helped drive Equity and Real Estate markets to well above historical valuations, benefiting the users and their investors. However, given what we’ve seen since late-07 and the subsequent tightening of credit and leverage, is allocating capital to these areas the best strategy going forwards?

My final concern is that many illiquid strategies require advance commitments for funding. Endowments have generally been willing to over-commit vs. their target allocations with the intent of using cash from the successful exit of existing investments to fund future investments. For example, per Yale’s Annual Financial Report, they have $7.5bn+ of unfunded commitments to Private Equity, or almost 50% of the endowment’s total value. This makes complete sense if the standard assumption is that prices are constantly rising, but it also creates a short-option position for the endowment. How?

Well, a down market results in the investor failing to receive their expected cash back (because returns are bad) and/or it takes longer for the cash to come back (e.g. the PE firm can’t IPO the business due to ‘market conditions’ so has to wait to do so). This results in new investments having to be funded out of cash or by selling liquid investments, which creates the short option position. I believe that endowments should count this short option position against illiquid investments and as result undersize rather than oversize them. Especially given that a fall in public equity markets already results in an increased allocation to illiquid markets before the above-mentioned cycle begins. This impact was clear in Jun-09, when both Yale and CalPers (amongst others) increased their target allocation to private equity to reflect the reality of their already increased exposure.

Trusting Efficient Market Hypothesis(“EMH”) and Modern Portfolio Theory (“MPT”) – Why?

One of the arguments for having these alternative assets in the portfolio is that they are less/ un-correlated with equities and bonds. However, this begs the interesting question… what time period do you use for correlations? If you truly believe that an endowment is permanent then you should use long-term ones (e.g. 10 or 30-year correlations). However, if you do that then the endowment and the institution associated with it have to accept that there will be a big down year (and hence budgets will have to be cut, people let go, etc) when the assets correlate. Can endowments really do that and are they willing to live with the consequences Siegel’s paradox?

In addition to this, there are the myriad of well-known problems with the EMH and MPT, the most important of which being the normality assumption. The conceptual conclusion of MPT is that asset-specific risk (non-systematic risk) is minor compared to asset-class risk (systematic risk) but this is dependent upon the assumption that investment risk is normally distributed. However, research has continually found that this normality assumption does not hold true for equities and bonds, let alone other (leveraged and illiquid) assets, resulting in a far larger left tail. Or more simply put, actual losses are regularly far higher than the expected losses.

Why have static allocation targets?

The faith in EMH and MPT leads to a broader question - why have static allocation targets? Shouldn’t the targets be dependent on the risk (i.e. shouldn’t price and ‘value’ matter)? While endowments may well have a long-term time horizon, this presumably does not obligate them to ignore current or medium-term information. One would think, as the attractiveness of asset classes changed both compared to their respective fundamentals and to other asset classes, the allocations would change. However, this seems not to be the case with the target allocations changing slowly (normally annually) and by very small amounts. The largest single reason was mentioned early in Part A, and is related to EMH/MPT, a focus on return targets!

A large part of finance, in particular in equity & equity-orientated world, asks us to believe that you can calculate an expected return for something. Couple with This is EMH/MPT telling us that the volatility is an appropriate measure of risk. It has resulted in a general belief that expected returns (i.e. target returns) are defined and inputs with that the level of risk that we take to achieve them merely being an output. As those of you who stumble to this blog will know, my opinion is the opposite of that; I find it easier to understand the level of risk that I’m taking, and allocate my capital to risk-related buckets, and view the return as an output of those decisions.

How else can one explain why endowments hate bonds (especially sovereign) and cash so much, yet adore equity-orientated strategies. Especially when you consider the propensity of sovereign bonds (particularly the US) to perform strongly at the time when an investor needs them the most; when equities suffer. As for cash, I’ve talked before on the blog about the positive optionality that cash offers; especially when times are uncertain, possessing it makes future decisions easier and allows you to be greedy when everyone else is fearful. In fact, for an endowment that’s heavily invested in illiquid strategies and barely any bonds, I would think holding a large amount of cash would be a prerequisite given the short optionality position that they face.

Given that endowments choose not to hold cash (or even more bizarrely hold negative amounts of cash by directly employing leverage) I can only posit that they must believe in the quaint notion that the value of assets must always be upward-trending and cannot possibly fall.

Until such time as Endowments recognize risk at the core of their portfolio allocation decisions, they are likely to be ‘shocked’ by years like 2008, and have to deal with the consequences of Siegel’s paradox. As my regular readers will know, my personal view is that that we have had a 25year+ era of increasing use of credit and leverage that has hidden many of the flaws in the markets and created numerous investing myths (starting with “markets are self-correcting”). Thus, while the Endowment Model represents a truly excellent way to have invested over the last 25-years, I believe that its lack of consideration for risk and its inflexibility means that it will likely fail to meet the needs of non-profit institutions going forward, something that I fear will be proved spectacularly over the coming decade.

Given that an endowment is there to support an institution (be it a foundation or a university) the level of risk that an endowment takes should be related to how the institution uses the annual. For example, Universities that get a significant percentage of their operating revenue from endowment disbursals (e.g. Princeton at c45%, Yale at c45%, Harvard at 35%, etc) should have different investment and risk objectives for their endowments than those where the disbursals represent a minimal amount of operating revenue. Larger endowments (in terms of disbursals as % of operating revenue) should be more risk averse than smaller ones, unless the institution is prepared to make significant cuts in its operating budget (e.g. by firing professors, doctors, etc or substantially reduce grants) every time there’s a noticeable fall in the endowments value. As such, can an endowment really be considered permanent when it provides a significant part of the operating income of the attached institution?

Illiquidity and being Short an Option

If we go back and look at the Endowment Model and how Harvard and Yale’s endowments have changed over time - we can see a reduction in fixed income and listed equities. Based on Mebane Faber’s work; at Yale between 1985 and 2008, Fixed Income (10.3% to 4%), Cash (10.1% to -3.9%) and Equity (67.9% to 25.3%) were all sources of cash. They were replaced by investments in Private Equity, Real Assets and Absolute Return strategies. This represents both a move towards more illiquid equity-orientated strategies and a subtle increase in leverage (as a result of investing in strategies, and outside managers, that employ leverage).

Unquestionably, one of Harvard and Yale’s great successes was realizing in the late 80’s and early 90’s that there was substantial illiquidity premium to be reaped by those investors who had a longer-time horizon. However, with the publicizing of the Yale model, and the move by others to copy it post-2000, does that illiquidity premium still exist?

Harvard and Yale’s macro call on the use of leverage has also proven to be successful – as investments that rely on leverage have benefited over the last 20years from the increased availability and low cost of credit. The use of credit and leverage has helped drive Equity and Real Estate markets to well above historical valuations, benefiting the users and their investors. However, given what we’ve seen since late-07 and the subsequent tightening of credit and leverage, is allocating capital to these areas the best strategy going forwards?

My final concern is that many illiquid strategies require advance commitments for funding. Endowments have generally been willing to over-commit vs. their target allocations with the intent of using cash from the successful exit of existing investments to fund future investments. For example, per Yale’s Annual Financial Report, they have $7.5bn+ of unfunded commitments to Private Equity, or almost 50% of the endowment’s total value. This makes complete sense if the standard assumption is that prices are constantly rising, but it also creates a short-option position for the endowment. How?

Well, a down market results in the investor failing to receive their expected cash back (because returns are bad) and/or it takes longer for the cash to come back (e.g. the PE firm can’t IPO the business due to ‘market conditions’ so has to wait to do so). This results in new investments having to be funded out of cash or by selling liquid investments, which creates the short option position. I believe that endowments should count this short option position against illiquid investments and as result undersize rather than oversize them. Especially given that a fall in public equity markets already results in an increased allocation to illiquid markets before the above-mentioned cycle begins. This impact was clear in Jun-09, when both Yale and CalPers (amongst others) increased their target allocation to private equity to reflect the reality of their already increased exposure.

Trusting Efficient Market Hypothesis(“EMH”) and Modern Portfolio Theory (“MPT”) – Why?

One of the arguments for having these alternative assets in the portfolio is that they are less/ un-correlated with equities and bonds. However, this begs the interesting question… what time period do you use for correlations? If you truly believe that an endowment is permanent then you should use long-term ones (e.g. 10 or 30-year correlations). However, if you do that then the endowment and the institution associated with it have to accept that there will be a big down year (and hence budgets will have to be cut, people let go, etc) when the assets correlate. Can endowments really do that and are they willing to live with the consequences Siegel’s paradox?

In addition to this, there are the myriad of well-known problems with the EMH and MPT, the most important of which being the normality assumption. The conceptual conclusion of MPT is that asset-specific risk (non-systematic risk) is minor compared to asset-class risk (systematic risk) but this is dependent upon the assumption that investment risk is normally distributed. However, research has continually found that this normality assumption does not hold true for equities and bonds, let alone other (leveraged and illiquid) assets, resulting in a far larger left tail. Or more simply put, actual losses are regularly far higher than the expected losses.

Why have static allocation targets?

The faith in EMH and MPT leads to a broader question - why have static allocation targets? Shouldn’t the targets be dependent on the risk (i.e. shouldn’t price and ‘value’ matter)? While endowments may well have a long-term time horizon, this presumably does not obligate them to ignore current or medium-term information. One would think, as the attractiveness of asset classes changed both compared to their respective fundamentals and to other asset classes, the allocations would change. However, this seems not to be the case with the target allocations changing slowly (normally annually) and by very small amounts. The largest single reason was mentioned early in Part A, and is related to EMH/MPT, a focus on return targets!

A large part of finance, in particular in equity & equity-orientated world, asks us to believe that you can calculate an expected return for something. Couple with This is EMH/MPT telling us that the volatility is an appropriate measure of risk. It has resulted in a general belief that expected returns (i.e. target returns) are defined and inputs with that the level of risk that we take to achieve them merely being an output. As those of you who stumble to this blog will know, my opinion is the opposite of that; I find it easier to understand the level of risk that I’m taking, and allocate my capital to risk-related buckets, and view the return as an output of those decisions.

How else can one explain why endowments hate bonds (especially sovereign) and cash so much, yet adore equity-orientated strategies. Especially when you consider the propensity of sovereign bonds (particularly the US) to perform strongly at the time when an investor needs them the most; when equities suffer. As for cash, I’ve talked before on the blog about the positive optionality that cash offers; especially when times are uncertain, possessing it makes future decisions easier and allows you to be greedy when everyone else is fearful. In fact, for an endowment that’s heavily invested in illiquid strategies and barely any bonds, I would think holding a large amount of cash would be a prerequisite given the short optionality position that they face.

Given that endowments choose not to hold cash (or even more bizarrely hold negative amounts of cash by directly employing leverage) I can only posit that they must believe in the quaint notion that the value of assets must always be upward-trending and cannot possibly fall.

Until such time as Endowments recognize risk at the core of their portfolio allocation decisions, they are likely to be ‘shocked’ by years like 2008, and have to deal with the consequences of Siegel’s paradox. As my regular readers will know, my personal view is that that we have had a 25year+ era of increasing use of credit and leverage that has hidden many of the flaws in the markets and created numerous investing myths (starting with “markets are self-correcting”). Thus, while the Endowment Model represents a truly excellent way to have invested over the last 25-years, I believe that its lack of consideration for risk and its inflexibility means that it will likely fail to meet the needs of non-profit institutions going forward, something that I fear will be proved spectacularly over the coming decade.

Monday, June 7

Chartology Redux: The latest charts that have caught Our Man’s eye...and why!

1). The Dollar (as shown by the DXY Index)

How things change! Three-Six months ago, and the poor old Greenback couldn’t find any friends. Now it’s threatening its 2008 flight-to-quality highs. Why’s it interesting; well, the dollar not been particularly strong for the last 15 years. Sure in 2000-2002 and 2008 it found a good flight to quality bid, but other than that it’s been pretty weak. However, for the one other occasion of dollar strength think back to the late 90’s Asian crisis and how it was preceded by a strong dollar rally.

2). M2 and M3 collapsing.

The monetarists amongst us claim that the FED’s money printing ways in 08-09 will inevitably lead to hyperinflation. Yet, over the last few months, M2 and M3 (as seen below, courtesy of Shadow Stats) have reversed course and are tumbling, in M3’s case at a speed not seen since the 1930’s.

Until we see a pick-up in lending, and the transmission of money from the asset markets to the real economy, we’re going to struggle to see the promised hyper inflation.

3). On the negative side, the Consumer Metrics contraction watch, is not pretty.

4). Adding to that, the leading indicators are tumbling.

Given my broad thoughts on some of the lessons we should learn from Japan (here and here), this is a big reason why I have no real interest in adding to my equity exposure (specifically the Water Thesis and the unwritten, so far, Lead-Acid Battery thesis) – I think I’ll be able to get them cheaper.

5). On the positive side, my favourite up-to-the moment snapshot of the economy, the ADS, shows no signs that its impacting the economy at the moment. In fact, it suggests thinks are looking quite peachy.

6). It seems like a long time ago, but we talked about the important of thinking about levels vs. changes.

Yes, the changes are dramatic (especially when using year-over-year in a world in flux) and that makes for interesting news-copy and something for talking heads to prattle on about. But it’s the levels that matter. In short, it’s fantastic the unemployment claims are down from their peak and that auto sales have risen from their lows but just look at the levels.

(Below, courtesy of Calculated Risk)

I’m not saying that the levels cannot, will not or should not rise from here, indeed they may well. However, for anyone whose base case is that they will then you’re already pricing in some level of GDP growth as your base case, and your risk management antennae should be well aware of that as more news comes out.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)